Code-wise, cloud-foolish

Avoiding bad technology choices in 2020

To be "penny-wise and pound-foolish" is to obsess over small savings while making expensive mistakes -- for example, spending huge amounts of money on a credit card just to redeem a few rewards points.

In 2020, resolve with me not to be "code-wise, cloud-foolish."

As technical decision-makers, our intuition often tells us that the "cheapest" solution to solve a problem (ie, the one with the best cost/benefit tradeoff) is one that:

Uses technologies we are already comfortable with

Gives us a sense of control by using open-source or vendor-agnostic software

Incorporates custom code and tooling where existing off-the-shelf options are pricey or otherwise unappealing

You could sum up all these rules as a bias toward the familiar. It feels good to use programming languages and tools that we know and trust. There is immediate, positive feedback when you create a slick deployment script because CloudFormation is too slow, or throw your data in Postgres because it "just works". Our pattern-matching brains tell us that this is smart engineering.

Unfortunately, this kind of thinking can be *code-wise, cloud-foolish*.

Code-wise, cloud-foolish thinking uses custom code to accomplish **non-differentiated** tasks that cloud services already perform.

Many of us have internalized the call to choose boring technology. The least-boring technology you can choose is one you have to write yourself. For any given problem space, the code you just wrote has the fewest users, the most bugs, and the least features of any code in the world. That is a necessary first step if existing technology is truly far from solving your problem. Otherwise, you just created something of negative value.

Maintaining a bespoke codebase, training new team members on it, handling operational issues, and adding features is expensive. For many (most?) teams, the cost of rolling your own deployment orchestration system, DSL, or Javascript framework will grow less and less acceptable over time. Save that overhead for the most important things, things that define and differentiate your business.

Another tricky bit of code-wise, cloud-foolish thinking: using languages and frameworks that make you feel good, whether or not they are the best tools for the job.

I don't take any joy in stoking the eternal flame war between declarative and imperative "infrastructure as code" tools. I don't like YAML any more than you do.

But it's been my experience that the "imperative" tools, which let you define cloud infrastructure in general-purpose programming languages, open themselves up to arbitrary complexity based on the whims of their users.

Sure, it feels good to write a bunch of for loops and class abstractions to build out a fleet of servers. But it's also easy to introduce logic errors and hard to communicate to other team members what you've created. That's why imperative deploy scripts, over time, tend to become spooky black boxes.

A declarative config file is often gross and verbose, but there's only one way to interpret it. Don't let your development preferences be the enemy of your team's ongoing success here.

Finally, code-wise, cloud-foolish thinking believes that you can hedge against lock-in by avoiding cloud best practices in favor of lowest-common-denominator "cloud-agnostic" solutions.

Cloud-foolish thinking overlooks that open-source technologies have their own forms of lock-in, sometimes quite insidious. Kubernetes is a great example.

I refer to Kubernetes as "Trojan-source software". Remember, it came from Google, a cloud provider. Engineers buy it for code-wise, cloud-foolish reasons:

It's built on deceptively familiar paradigms (containers)

It's open-source; you can theoretically run it anywhere

Here's the problem: K8s is so complex that we avoid even spelling out the word, like it's the Hebrew name for God. The orchestration and configuration requirements to run it in production are far beyond many teams' comfort level. That's why hosted versions of Kubernetes like GKE and EKS are so popular.

When your open-source software is so complex that it effectively requires a cloud provider to run it on your behalf, you've stumbled into back door lock-in. And you don't even get the advantage of traditional cloud lock-in, which is deep integration between native services.

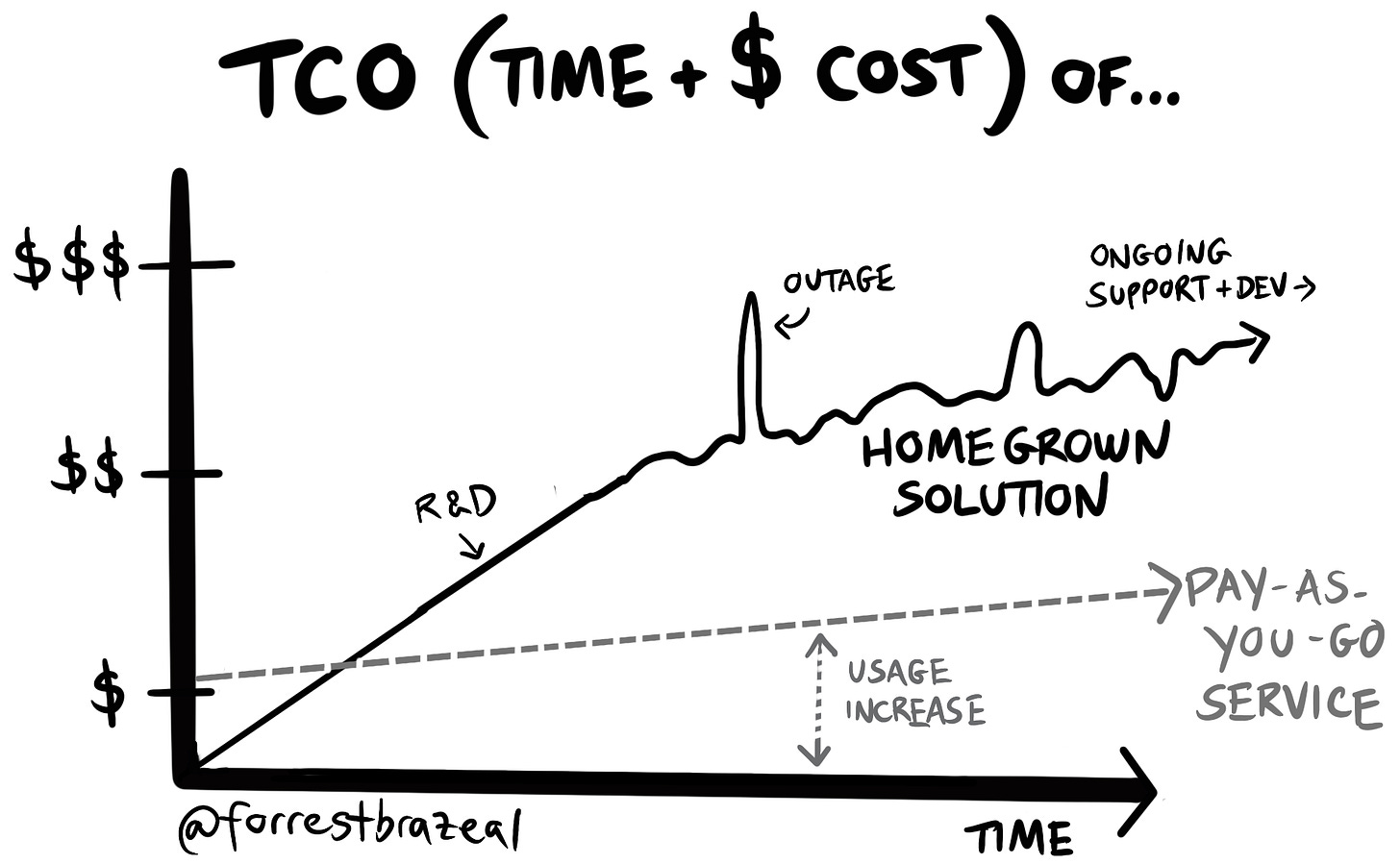

This is not to say that you will always be happy with the decision to consume a cloud-native service (or use any form of pre-existing technology). I have frequently made bad adoption choices. In graphic form:

But due to the lower fiscal and emotional investment, I typically feel much less pain when it's time to move away from a managed service than if I have to sunset something I built.

Anyway. You wouldn't incur massive credit card debt just to get a few free hotel nights. So don't spend your limited innovation credits building bespoke, complex systems that provide no direct value to your business.

Instead, build on something like The Good Parts of AWS to position yourself at the top of what I call the Wisdom/Cleverness Curve:

Have a productive and happy 2020. Be cloud-wise.

Links and events

Another AWS re:Invent has come and gone. I wrote about new observability services, the hidden costs of Lambda provisioned concurrency, and collaborated on this deep dive into Lambda Destinations.

Jeremy Daly and I sat down with RedMonk's KellyAnn Fitzpatrick to discuss CI/CD on AWS:

If you're looking for a roundup of all my cloud-related writing from 2019, look no further.

Just for fun

The only accurate predictions for the 2020s:

Serverless still has servers.

Bitcoin gets regulated, but scores a religious tax exemption.

The gig economy reaches the public sector, as most schools and municipalities are now staffed via TaskRabbit.

The USA elects two rival presidents simultaneously. This is not constitutional, but neither is much else.

Misunderstanding the phrase everyone has been telling them, Oracle continues its desperate bid for relevance by launching a streaming service called Oracle Go.

Apple acquires the entire entertainment industry in an all-cash transaction. Apple TV+ gets three new scripted shows.

Generation Alpha, the children of millenials, are finally old enough to sue their parents for using them as props on Instagram.

The 2020s last for ten years, none of which turns out to be the year of Linux on the desktop.